Last week, eight US senators urged President Joe Biden to order a security review of the global network of undersea communications cables, citing the “threat of sabotage” by Russia – and China.

It was just the latest expression of US concern over China’s potential espionage in handling network traffic, an accusation Beijing has repeatedly rejected.

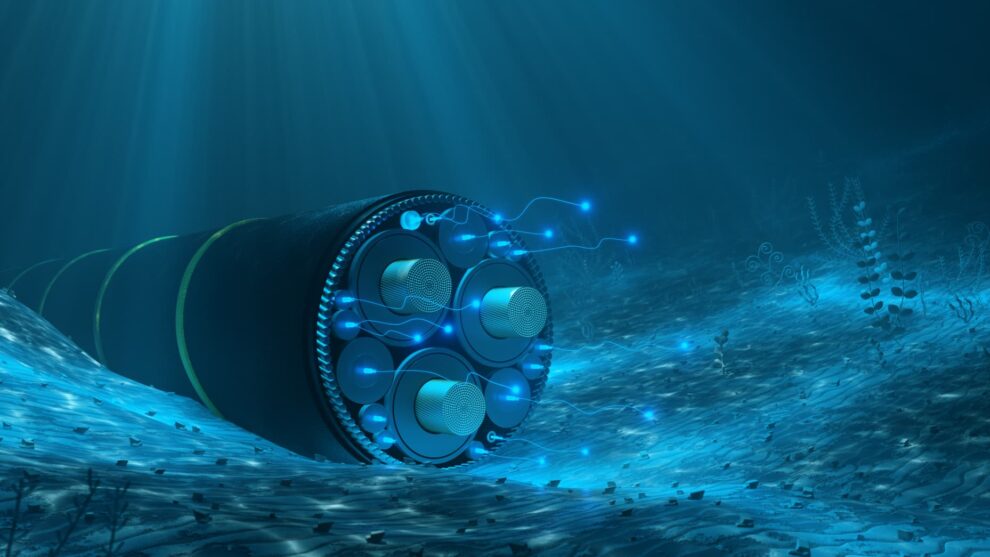

Usually running along the bed of the world’s seas, undersea cables are the backbone of the global internet for daily communications.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

About 95 per cent of the US population and nearly 75 per cent of China’s use data that is transferred through undersea cables, and the number is growing.

As global powers jockey for technological and economic supremacy, undersea cables are increasingly at the centre of the competition.

Here are five things to know about the undersea information network, and what it means to the US-China relationship.

Undersea cables, also called submarine cables, are fibre optic cables laid on the seabed between land-based stations. They carry up to 99 per cent of internet traffic between continents and are vital for transmission of data, from personal email, online shopping to scientific research.

Financial transactions on platforms like banking networks, like Swift, as well as fintechs and blockchains also depend on data traffic through the cables.

The first undersea cable was laid in 1850 between France and Britain, and as of September, there were 532 active undersea cable systems, with another 77 planned, according to telecommunications research company Telegeography.

Their importance to national security

Data is now a driving force of digital economy, and data security has become vital to not only economic security but also the national security of governments around the world.

While undersea cables are buried in the sea – at some points as deep as 8,000 metres (five miles) to protect against potential damage by fishing trawlers – this data infrastructure is not always safe.

In 1914, when Britain entered World War I, it cut German telegraph cables under the sea, forcing the Germans to shift to radio communication that was easier to intercept.

During the Cold War, the US Navy tapped into the Soviet Union’s undersea communication cables at the Sea of Okhotsk near Japan, listening in on sensitive military communications between Soviet naval bases.

Today, submarine cables are an important component of communications security, especially for coastal states.

“Having enough submarine cables is necessary to ensure resilient connectivity to global networks and, ultimately, the digital economy,” said Lane Burdette, a research analyst with Telegeography.

They are also “an important strategic component in maintaining national security”, Liu Dian, a researcher at the China Institute of Fudan University, said.

“For a country, having control over key submarine cable routes means that it is able to influence and even control the flow of data to certain countries or regions,” Liu wrote in Current Affairs Report, a magazine published by Chinese Communist Party’s central propaganda department.

Undersea cables are built, operated and maintained by private companies.

The global cable-manufacturing-and-laying industry used to be dominated by western companies, including SubCom in the US, NEC in Japan and France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks.

In 2008, though, Huawei Technologies founded Huawei Marine, a submarine cable joint venture with the British company Global Marine Systems offering services such as system design, installation and integration. The company quickly grew to become the world’s fastest-growing subsea cable builder.

As geopolitical competitions intensify, Beijing has repeatedly stressed the importance of controlling critical technology, and investment in undersea cable technologies has become a priority as it aspires to become a great maritime power.

In 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology released its five-year plan, in which it stressed the support of “national shipbuilding” of undersea cable repair vessels. Last year, China launched two large home-made cable layers, Long Yin 9 and Qi Fan 19, each of which can carry 10,000 tons of cable.

Tensions about the underwater infrastructure drew media attention in May 2019, when Huawei Marine, together with Huawei Technologies and its 67 non-US affiliates were added to the US “entity list” that restricts access to certain products and technologies.

Months later, Huawei decided to sell its stake in Huawei Marine to Hengtong Group, China’s largest power and fibre cable manufacturer, and the firm was later renamed HMN Tech.

In April 2020, following opposition from the US Justice Department, Google and Facebook withdrew plans for a Pacific Light Cable Network to connect Los Angeles and Hong Kong with a 13,000km (8,000-mile) internet broadband cable that US officials said could expose Americans’ data to Beijing.

The US State Department also launched the Clean Network Initiative, which sought to ban new cables from connecting the US to Hong Kong and China directly.

Last year, the US House of Congress passed the Undersea Cable Control Act, which sought to prohibit Chinese companies from gaining access to undersea cable-related goods and technologies in the US. The bill still needs Senate approval before being signed by the president.

The US has also ramped up coordination with its allies to prevent China from becoming a major presence in undersea cables, including working with its partners Japan, Australia and India in the Quad security dialogue to invest in undersea cables in the Indo-Pacific.

Last month, Reuters reported that the US has told Vietnam to avoid Chinese vendors, including HMN Tech, in its plans to build 10 new undersea cables by 2030.

Beijing has repeatedly rejected espionage claims, which it said were “created out of nothing”, and has accused the US of using its “small yard, high fence” investment restrictions to suppress China’s development.

China has stepped up investment in undersea cables in the Global South, including in South America and Africa. One high-profile project is the Peace Cable, a 15,000km project connecting Pakistan, Singapore, Cyprus, Egypt, France and Malta that has been operating since August.

Will competition escalate?

The US actions appear to be working.

According to Burdette, the TeleGeography analyst, between 2010 and 2023, HMN Tech provided an estimated 10 per cent of all new kilometres of cable entering service. However, for cables planned for this year through 2026, that percentage drops to 4 per cent.

“It seems that US and allied pressure against using HMN Tech for new submarine cables may be having an effect,” she said.

Since the Pacific Light Cable Network was denied a landing license by the US Federal Communications Commission in 2020, no new cables have entered service that directly connect the US to China.

And yet a true decoupling is unlikely. The two countries are still connected digitally, as data from one side passes over multiple submarine cables before reaching the other side of the Pacific Ocean.